|

The Favorite Flowers of Japan

(1901):

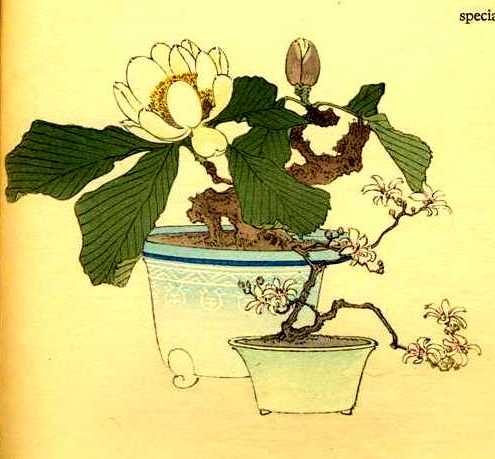

With the remembrance of the deep purplish-red, white and pink peonies of my grandmother's garden in mind, I started very unenthusiastically one morning in April for my first visit to a celebrated paeony garden in Tokyo. As we crossed the small front garden, I stopped to look at the dwarf trees, always fascinating to a new-comer, wondering why my friends pushed forward so eagerly. (pg. 17)

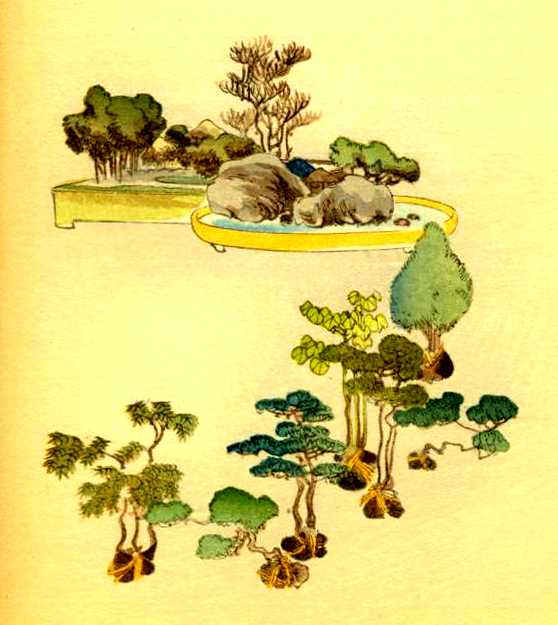

The process, which to the stranger seems so

mysterious, is really rather a simple one. The gardener prefers

to select his trees from the forest and, after severely trimming back

the branches and roots, he plants this skeleton in a very small

receptacle, the size and shape of which is dictated. The branches

are tied down and if a branch grows out of proportion it is judiciously

clipped so that this diminutive tree may resemble its brother of the

forest. The plant is left in the same earth as long as possible

and is only repotted when absolutely necessary. Just enough water

and nourishment are given to keep it barely alive and in this very

tenacity with which the tree fights for existence is seen reproduced

that tale of a long life of strife and struggle against adversities,

which makes those gnarled old mountain trees so dear to the Japanese.

(pp. 49-51)

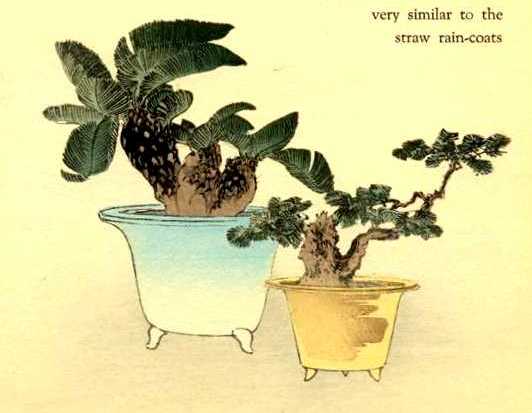

Cycas revoluta

(left specimen, pg. 56)

1 |