Last Updated: March 16, 2025

|

When Tokugawa Ieyasu's son, Hidetada

(r.1616-1623), abdicated, his nineteen-year-old son

Iemitsu became the third

Tokugawa shōgun (r. 1623-1651).

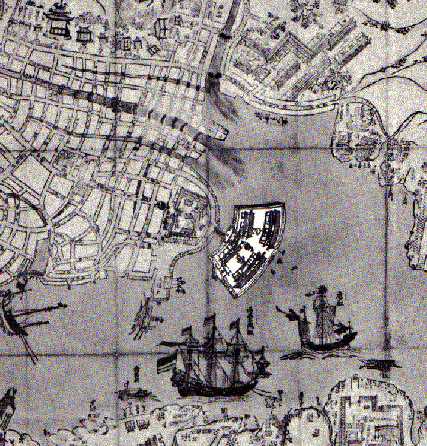

Iemitsu devoted all his time to the study and perfecting of government methods introduced by Ieyasu. In 1621 fire leveled all of Edo (old Tōkyō), including structures in the castle compound. Within two years fortress-like city mansions were being built and more tideland area was being reclaimed. Iemitsu achieved dual influence in 1630 when his seven year-old niece became Empress Myōshō (aka Meishō) in Kyoto. Four years later Iemitsu visited her in Kyoto. The following year, his sankin-kōdai law decreed that all 270 daimyō (lit., "Great Name") or feudal lords build mansions in Edo, leave their families there at all times (well attended to by close to 80,000 retainers and servants), and the daimyō themselves spend every other year in Edo in attendance at the shōgun's court. (Perhaps Iemitsu took a hint from China's Qin Huang Di, who eighteen centuries earlier had similarly decreed his nobles to stay nearby.) The wives and children left behind were a guarantee of the daimyō's good behavior, and strict scrutiny at various check-points prevented these hostages from slipping home. Another great burst of building took place in Edo. The Tōkaidō highway was the great road which connected Kyoto and Edo. The daimyō's processions were elaborate and very expensive affairs with a large number of retainers in attendance keeping the highway congested. Some of the daimyō, impressed with the landscapes travelled through and nearby on their way to their Edo residences and back every other year, contracted to have these scenes reduced in scale and reproduced along the pathways of their gardens in Edo and/or in their administrative jurisdictions. (Perhaps they also used these "maps" to update family members upon the daimyō's return to Edo.) As the Edo period progressed, the building of artificial miniature mountains, copies of actual mountains such as Mt. Fuji, became popular. Now, Ieyasu had made Edo his capital when he became shōgun in 1603. Over 600,000 men were reported to have been brought to Edo by their daimyō to work on the walls and fortifications of the castle there, which originally dated from 1457 and which had raised Edo up from being a mere fishing village surrounded by marshes. Ieyasu's castle, covering an area some ten miles in circumference, was not completed until 1636, during the reign of his grandson Iemitsu. (The building would be destroyed several times by fire, but the moat and walls still remain as a fitting setting for the residence of the current Emperor of Japan as the Imperial Palace.) The year 1636 also saw the completion of two years of construction of Ieyasu's ornate mausoleum at Nikkō, some 145 km (90 miles) north of Edo and set in magnificent scenery. Iemitsu closed Japan entirely to most foreign commercial transactions, permitting only limited numbers of Dutch and Chinese, the former because they were not Catholics. In 1641 the Dutch were assigned to the six hundred by two hundred and forty foot island of Deshima. The hardships of virtual imprisonment by the severe and strict government of Nagasaki and avoidance of all outward signs of Christianity were felt to be a small price for the continued Japanese trade.

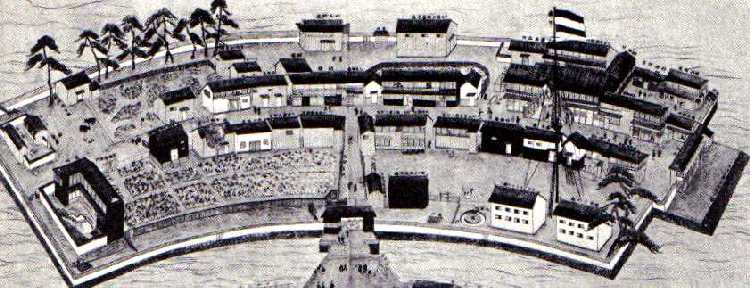

Deshima was a three-acre (130,000 sq ft) fan-shaped artificial island in Nagasaki harbor built in 1635 and connected only by a heavily guarded bridge to the city. The Dutch, who had uncovered evidence of a traitorous plot by the Portuguese, were installed as the sole European exception. On the island was a street of two-storey buildings whose bottom levels were for warehousing and upper levels for the living quarters.

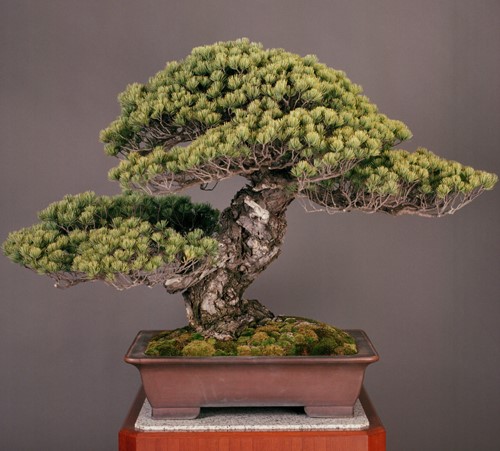

There were over a hundred Interpreters assigned to Deshima, so that it would be unnecessary for the Dutch to learn Japanese, and by this means the Dutch could be kept ignorant of local conditions, commerce, history, and so forth. Any Dutchman who showed progress in learning the language would, under some pretext or other, be put on board the next outbound ship. In the best years there were perhaps seven trading ships annually dropping anchor at Nagasaki, and each was searched upon arrival and before departure. The Japanese officers were solemnly bound neither to talk to the Europeans except as trade required, nor to make any disclosures regarding domestic affairs of Japan, its religion, or its politics. These stringent regulations were somewhat relaxed in such matters as the Dutch language, astronomy, natural history, and medicine, especially if orders came from high official circles to make specific enquiries of the Western Barbarians. (See also this early bonsai connection to Deshima). Three Chinese temples with monks were founded in Nagasaki after the Catholics were expelled. In the seventeenth century, monks of Japanese Zen Buddhist temples visited China and brought back paintings -- including some actual Chinese literati ones -- and many books. Some of these monks even painted in Chinese-derived styles. Also, a few relatively minor Chinese painters visited Japan during this time -- were they allowed past Nagasaki? It should be remembered that even after 1639, when the Dutch were the only Europeans permitted to remain in Japan, the Chinese continued trading there on far more advantageous terms, supplying the bulk of Japanese lacquerware to the rest of Asia and Europe. Japan cut back trade with China when it was discovered that the Jesuits were favorably treated at the Chinese Court, by whom the missionaries had liberty granted them to preach and propagate the Gospels through all the vast dominions. When Iemitsu died in 1651, five daimyō performed junshi. This was originally the practice of burying retainers alive after the death of their master, but it later had become the custom of committing suicide on the death of one's leige lord. The custom was supressed by Iemitsu's son, shōgun Ietsuna, in 1668. Additional biographical details can be found here. 1 THE PINE Iemitsu, the fiercely nationalistic third Tokugawa shōgun was -- possibly surprisingly -- an enthusiast of hachi-no-ki, horticulture in general, painting, and the tea ceremony. In terms of gardening for pleasure in Edo, shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu was the first to get the ball rolling. Despite his reputation for being a somewhat unsophisticated man, Ieyasu was very fond of flowers, as was his son, the second shōgun, Hidetada. The third shōgun, Iemitsu, surpassed both his father and grandfather in his passion for gardening. All three were particularly ardent fans of the camellia. With the ruling family so enamoured of gardening, many daimyo felt that it would be prudent to follow suit. Their estates in Edo were soon transformed into veritable farms, with vegetables and medicinal plants grown alongside ornamental plants and flowers. Not only did the daimyō present flowers to the Tokugawa family as gifts, the ruling family also bestowed gifts of potted plants and seedlings upon their retainers. Allowing these plants to die would have caused great offense to the shōgun, which added considerably to the burden of those tasked with keeping them alive! Iemitsu himself planted seedling trees in tiny pots, lined up the trees on shelves he had set up in the flower garden of his castle, and toyed with their well-ordered, delicate leaves. Occasionally, Iemitsu's enthusiasm and love for the art caused him to neglect his governmental duties. Thus comes the story during the Kanei era (1630-1644) of Ōkubo Hikozemon (1560-1639), councillor to the shōgun, who threw one of Iemitsu's favorite trees away in the garden -- right in front of the shōgun in order to dissuade him from spending so much time and attention on the trees. In spite of this servant's efforts, Iemitsu never gave up the artform he continued to love. Sandai-Shōgun-no-matsu ("Third generation Tokugawa's pine"), a five-needle white pine (goyo-no-matsu, Pinus parviflora var. negishi), is still living in the twenty-first century. Iemitsu cared for this and it has been passed down into the care of emperors. The tree was already close to 200 years old when Iemitsu first took possession of it. Especially fond of this celebrated pine, he assigned three attendants to its protection and care. The shōgun's special steward who took care of it was said to have been paid three to five times the normal stipend for his services. 2 Was the tree started in a pot-life from seed, nursery/garden plant, or collected yamadori, and where did it originate, approximately in the second half of the fifteenth century, around the time of the Ōnin War during the Muromachi Period? Who first potted this plant and when, and who cared for it before Iemitsu was introduced to it? Who had trained it before Iemitsu and how did this particular shōgun get possession of it? What containers was it in before, during, and after Iemitsu's ownership, and what types of styling and design has it been through in its life? It would have been known as a hachi-no-ki -- literally, a "bowl's tree," rather than a bonsai, a "tray plant" -- at the time. How big was its home and/or what type of rootball did it have? Close to 200 years old when Iemitsu had it, its trunk would have been only an inch/a couple of centimeters or so in diameter at that time. The tree's location and care for the next two centuries is only partially known to us. Has it been in the Edo area its entire life or was it brought in after the great fire of 1621? How large were its various dimensions allowed to grow through its life? How long were the branches that became jin, and when and why? When and why did the trunk become hollow, sabamiki? Was it called Sandai-Shōgun-no-matsu during or fairly soon after Iemitsu, or was there a formal/informal naming ceremony later? Who were the experienced people who obviously cared for it through the centuries? What natural or man-made disasters (including fires and earthquakes) actually threatened this tree through the years? What styles and containers did it have during its middle life? Were there any portrayals made earlier of what it looked like? (How many trees did Iemitsu have? Was the collection kept together or dispersed after Iemitsu's death? Is Sandai-Shōgun-no-matsu the only surviving specimen from that collection? When did the second last survivor pass away? See below for a partial answer.) What daimyō saw this pine while they paid visits to the various shōgun and others who cared for or possessed it? Did any of the horticultural writers or artists (here, here and here) ever see or hear about this specimen? Was it ever in any type of public display -- or would that have been considered too uncouth? Was it ever admired during a tea ceremony? Gardeners began to increase in Edo town after the Great Fire of Meireki (1657), a three-day-long blaze which destroyed 60-70 percent of Edo, and in combination with a severe blizzard that quickly followed, is estimated to have killed over 100,000 people A landscaping boom occurred during the town's reconstruction, creating a demand for gardening. A nurseryman, Itō Ibei/Ihee of Somei village in Edo (now part of Toshima City, Tokyo, a few miles north of the Imperial Castle), who called himself "Kirishima-ya," can be said to have led the horticultural world from the early Edo period to the mid-Edo period. Itō Ibei's attention to detail wasn't just about his deep knowledge of plants but also his ability to accurately grasp and analyze the trends of the time, making them viable as a business. It's noteworthy that in the Itō family, even as the main figure changed, the name "Ibei" was passed down through the generations, frequently appearing in history as important figures in horticulture. The family excelled in insight and expertise in landscaping and flower cultivation, leaving behind many works that depicted the types of horticultural plants that were popular at the time. The original Ibei was said to have been the best gardener in Edo; Kinshu Makura (A Brocade Pillow), the classic 1692 work by him was the first monograph on azaleas either in Japan or elsewhere; and he also got into Edo Castle to serve the shogun. The details are unknown, but it is said that Ibei was given the Goyomatsu, Sandai-Shōgun-no-matsu, by the shogun's family. It was probably as a reward, and the white pine went out of Edo Castle. In the 12th year of the Genroku era (1727), during the tenure one of Ibei's descendants, Itō Masatake, the 8th shogun at the time, Yoshimune, visited Ibei's garden/plant nursery and purchased twenty-nine varieties of plants including Kirishima Azalea, as recorded.

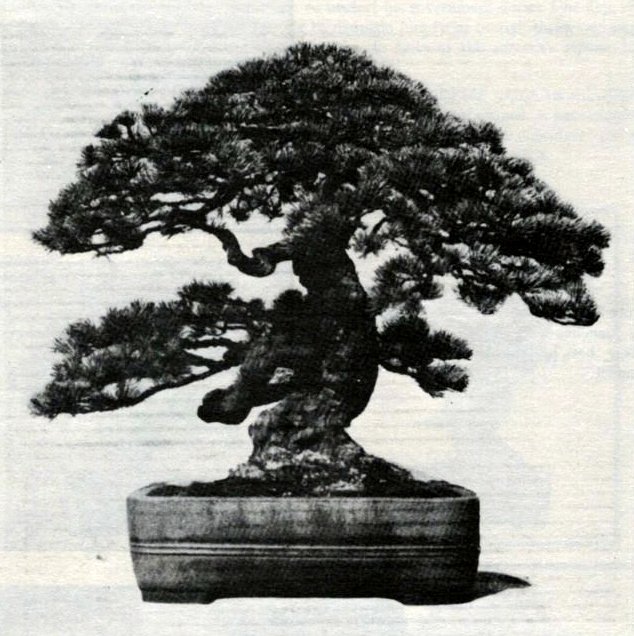

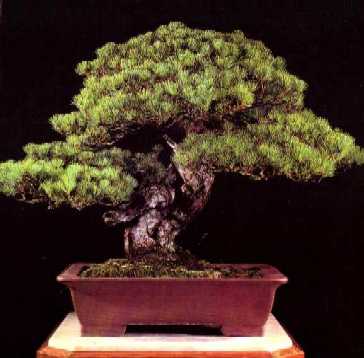

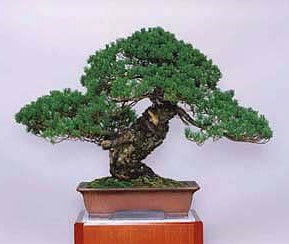

A photo taken after the war shows the Collection's Tokugawa Iemitsu white pine in neglected condition with much of its growth close and untrimmed. Its shape and that of many trees throughout the country had become very poor. A concerted effort to save and restore the Collection was then made by officials and bonsai lovers. Many a postwar fancier tried a hand at restoring or restyling some of the non-masterpiece trees. Sometimes it would take a decade or more of careful tending and re-training to make up for the neglect of those few angry years. But the tree survived and thrived.

More recently, the 82 cm (32.25") high tree was one of four bonsai as National Treasures in the "Exhibits of the Special Exhibition, commemorating the 20th Anniversary of the Enthronement of His Majesty the Emperor" Akihito in 2009. (Based on the more recent photos on this page, the estimated width of the foliage is about 165 cm or 65".) 5

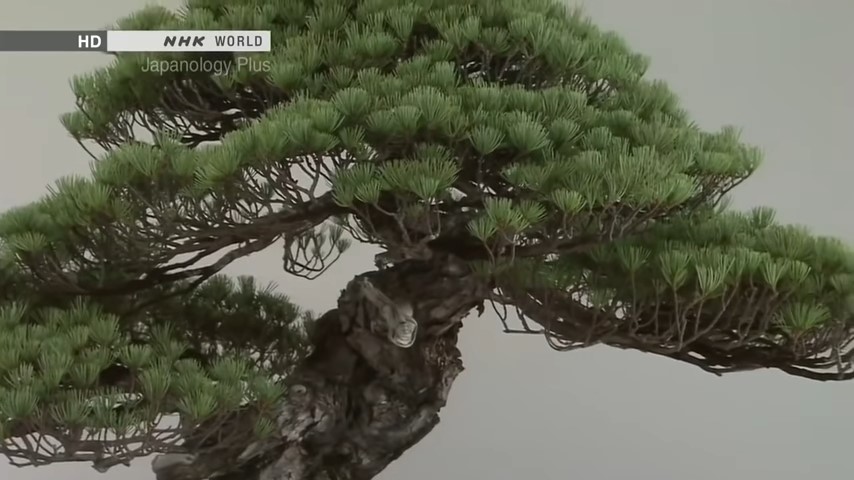

Starting at the 2:44 mark and going to 3:07 in this February

23, 2018 video, "Bonsai The Living Works Of Art

Japanology," The Third Shogun is too briefly seen with some close-ups of its wonderful short needles. There is also the story that a samurai's gardener killed himself when his master insulted a hachi-no-ki of which the artisan was especially proud. 6 Iemitsu had mountain cherries from Mt. Yoshino transplanted to the Kan'ei-ji temple, resulting in Ueno Hill where the temple was located becoming a popular location for Cherry tree viewing. (And tradition holds that in 1641 Iemitsu planted a certain gingko tree on the grounds of the re-built Tōshō-gū Shinto shrine in Shiba Park, south of the Imperial Palace. The large landscape tree -- 21.5 m (70.5') tall and 6.5 m (21.3') circumference about 1.2 m (3.9') above the ground -- was designated as a Natural Monument in 1956.) 7 |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|