" Hachi-No-Ki, A Perspective "

Originally published in the ABS Bonsai Journal, Vol. 26, No. 2, Summer 1992, pp. 3-4, 23.

© 1992 American Bonsai Society, reprinted by permission

Originally published in the ABS Bonsai Journal, Vol. 26, No. 2, Summer 1992, pp. 3-4, 23.

© 1992 American Bonsai Society, reprinted by permission

| Many books and articles giving a brief overview of bonsai history have made passing mention to the Japanese play Hachi-no-ki (The Potted Trees). Perhaps a handful have even given a one or two line synopsis of the piece. This current article seeks to provide some indepth background and understanding of this work. | ||||||||||||||||

| The play is apparently based on a 1383 folktale, and that story tells of a supposed incident during the life of the historical Tokiyori Hojo (1226-1263). Tokiyori, at age twenty, succeeded his brother as regent or governor to the Minamoto-clan shogun, the supreme military general. While the shoguns ruled, they and not the hereditary emperors guided the island nation. Tokiyori held his post for ten years, consolidating the regent’s power until his health began failing. Although he continued in fact to rule, Tokiyori shaved his head and retired to a monastery. He then travelled incognito through the countryside in order to see for himself the needs of the people and abuses of the administration. His time in government was marked by a wise economy and a close interest in agriculture. | ||||||||||||||||

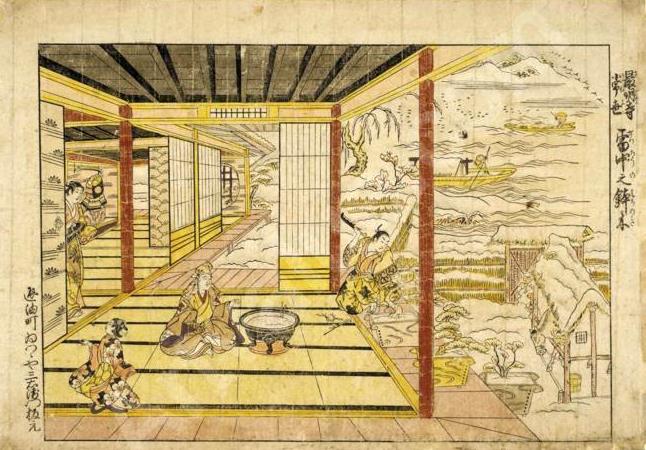

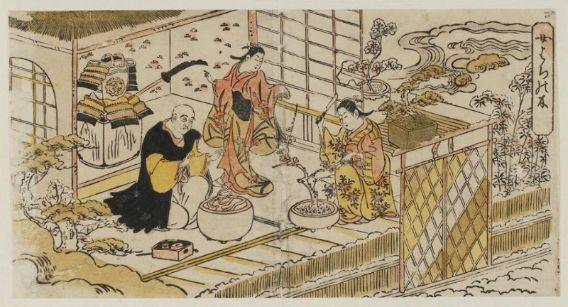

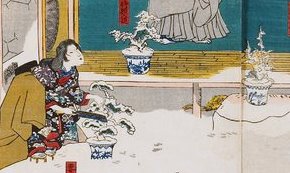

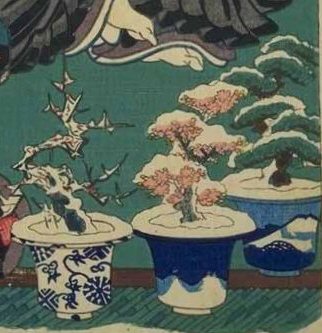

| The play itself is in two parts. In the first, a travelling monk, lost in the snow in the dead of winter, happens to come upon the meager residence of Tsuneyo Genzayemon. Formerly in Tokiyori’s employ, Tsuneyo once owned this land in the Sano area, but lost it through a relative’s deception. (If Tsuneyo was also a real person, his life’s story has been lost to history.) Tsuneyo and his wife, hesitant at first, offer what miserable accommodation they have to the traveller and share a poor peasants’ meal of a little boiled millet. To provide heat for this special occasion, but lacking any other fuel, the old man, with Buddhist resignation, decides to burn his only three dwarf potted trees. To the silently listening monk, Tsuneyo tells his story of suffering and poverty, and his long-held loyalty to the shogunate. | ||||||||||||||||

| In the second part of the play, which is set six months later, we find that the monk actually had been Tokiyori himself, travelling in disguise. Impressed with Tsuneyo’s kindness, and wanting to test his claims of loyalty, Tokiyori spreads a rumor from the capital city of Kamakura that war is imminent. An army of the finest and bravest soldiers assembles there to protect the shogun, in all their polished glory, on fattened steeds, with grooms beside them. Tsuneyo is there also, by himself, in worn-out armor, with rusty sword, and leading a slow, emaciated horse. Moved by the old man’s proven loyalty, Tokiyori rewards the impoverished samurai by restoring to him his former lands. In addition, three other pieces of land are deeded to him. The names of these include the words "Ume" (plum), "Sakura" (cherry), and "Matsu" (pine), in gratitude for Tsuneyo’s sacrificed trees. | ||||||||||||||||

| Hachi-no-ki has no definite authorship, but traditionally has been attributed to the playwright Zeami because of stylistic similarities to some of his other works. In fact, Zeami Motokiyo (1363-1444) was Japan’s Shakespeare. With the help of his father, Kan’ami Motosugu, he fused a mixture of secular entertainment, country songs and dances, and Shinto and Buddhist plays with classical literature. Both Zeami and Kan’ami were playwrights, actors, and composers. They also had the critically discerning patronage of Yoshimitsu, the young but politically astute Ashikaga-clan shogun. The classical tradition was revitalized and broadened in its appeal by Zeami’s plays and three major treatises on theater and aesthetics. According to various authorities, his plays numbered anywhere between twenty and ninety. These pieces were based on older plays, legend, or contemporary events, and initially were enjoyed by all levels of society. | ||||||||||||||||

| This new entertainment was eventually called simply "Noh" ("talent" as in "the display of talent in a performance"). It was adopted and nurtured by the Zen-dominated atmosphere of the court, and exemplifies the Zen combination of splendor used with restraint. Beautiful and heavily brocaded costumes surround male-only actors who perform minimal symbolic gestures and refined, extremely slow dance steps to deliberately sung or spoken text. The text is usually arcanely worded with many ancient poetic allusions and wordplays. A seated chorus is at stage-left, and at times either acts as narrator, or speaks for one or more of the characters. The stage itself is a curtainless, polished raised platform eighteen feet square, having the audience in front and at stage-right. A Noh theater is immediately recognizable by its unvarying painted backdrop of a huge pine tree growing in the ground. Sparse stage props are also to be noted. | ||||||||||||||||

| In Hachi-no-ki, a single pine branch held up by a square or circular form on the bare stage represents the three small trees to be sacrificed amid the play’s dominant themes of sorrow and purity. This particular play is fairly unique in Noh theater because of the Western-like linear treatment of time and space without the use of any supernatural intervention to develop the characters’ downfall and salvation. The starkness of the opening winter scene is also highlighted by the absence in Hachi-no-ki of what would otherwise be obligatory music for Tsuneyo’s entrance. Unlike many other Noh plays, where masks to represent specific characters or emotions are used, here, they are not worn. | ||||||||||||||||

| In the early 1600’s, the Tokugawa clan emerged as the shoguns and maintained peace for two and a half centuries. Their hold on power was, in part, due to numerous rules and decrees governing many areas of Japanese life. The Tokugawa ritualized Noh performances and music, and set out systems of precise rules and regulations for the four distinct Noh schools. Strict rules were also established for many other activities including flower arrangement, the tea ceremony, and the forming of hachi-no-ki (as Japanese dwarf tree culture was commonly called until the mid-1800’s). | ||||||||||||||||

| As official art and ceremony, Noh became so solemn and symbolic, with an appeal primarily to the educated aristocracy, that a more lively and spectacular form had replaced it for the general public: kabuki theater. Each five to ten page Noh text now took an hour or two to perform. | ||||||||||||||||

| Out of perhaps 2,000 Noh plays, some 800 or so works are extant, most of which were written in the fifteenth century. About 250 survive in the art's repertoire as consummate masterpieces of Japanese literature whose ritualistic enactment must be witnessed in performance with flute, drum and chorus to be truly appreciated. Hachi-no-ki is counted among these currently active plays. | ||||||||||||||||

| Specific excerpts from a very simple English rendering of the text offer insight into such tree raising at the time: | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| The term "hachi-no-ki" (literally "the bowl's tree") implies a deeper container than bonsai ("the tray's plant"). In the former, the art had not been developed enough to maintain a typical tree in what is now the characteristic shallow pot. | ||||||||||||||||

| By the evidence in this play, we cannot determine if such trees at the time in Japan were only gathered in the wild, or if some were at least partially formed by human intervention (with some trimming perhaps, or by way of rooted cuttings). We cannot necessarily say how big or small they were, how long they may have lived in their containers, or how much the trees conformed to any aesthetic ideals which we know were later applied to the art. Technical specifics are lacking, but that is not surprising considering the medium. | ||||||||||||||||

| The existence of this play indicate that some 600 years ago, dwarf potted tree culture was well-known enough in Japan to be a pivotal element in some piece of folklore which soon became retold in the theater of the court. Historical references within the story itself push back such gardening another century. At least these three types of plants were used, and possibly exhibited at that time, in the early stages of the art. It apparently was not unusual for even a minor member of the aristocracy to care for several trees, or even if reduced to poverty, to still keep a few for the beauty they offered. | ||||||||||||||||

|

There will continue to be disagreement over the date of the commencement

of the true practice of bonsai. We can conclude from this oft-mentioned,

but infrequently appreciated play, however, that some form of aesthetically

pleasing dwarf potted tree culture in Japan was indeed being practiced

to a notable degree long before the art included its present array of horticultural

techniques. For while skill does elevate and expand it, the origin

of any form of art lies in the appreciation of a thing of beauty.

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Thomas Blenman Hare, Zeami’s Style, The Noh Plays of Zeami Motokiyo ; Stanford, Ca.: Stanford University Press; 1986. | ||||||||||||||||

| Donald Keene, No, The Classical Theater of Japan ; Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd.; 1966. | ||||||||||||||||

| E. Papinot, Historical and Geographical Dictionary of Japan ; Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc.; 1972. | ||||||||||||||||

| Arthur Waley, The No Plays of Japan ; New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 1922. |

|

Per The Clear Mirror: A Chronicle of the Japanese Court During the Kamakura Period (1185-1333) translation by George W. Perkins (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press; 1998), pg. 228, Footnote 23 (onto pg. 10), "Chapter 9, is believed to be the source of the legend, immortalized in the Noh play Hachi No Ki (The Potted Trees), that Tokiyori traveled the country in monkish disguise to correct injustices.": "After taking the tonsure in the first year of Kōgen (1256), Tokiyori had traveled through the provinces as an anonymous wandering monk, with the intention of gaining firsthand information about local conditions and individual grievances. He once approached a dilapidated dwelling, inquired about the master's circumstances, and learned that the authorities had ignored a perfectly reasonable complaint. 'I can't claim to carry any weight myself, but I used to serve a lord of considerable consequence. I think he probably still wields some influence, so I'll write him a letter. Take it to him and tell your story,' he said." "The man thought, 'What can a beggar monk do for me?' But after talking the matter over with his relatives, he took the letter to Kamakura and stated his case, just as he had been told to do. The officials saw that the letter was from Tokiyori. 'Calm yourself!' they said. And they arranged matters so that the man would never have cause for complaint again. His whole household bowed their heads to the ground in joy, wondering if their visitor had been a god or Buddha in human form." "Thanks to countless other incidents of the same kind, officials in all the provinces took care to govern justly." "People called Tokiyori the Saimyōji Lay Monk." (from Chapter 9, "Pillow of Grass," pg. 112) "Tokiyori, Hōjō (1227-1263). Fifth Kamakura regent or shikken (1246-1256). Consolidated Hōjō hegemony in Kamakura. Second son of Tokiuji; grandson of Yasutoki. Yasutoki (1183-1242) was son of Yoshitoki and succeeded his father as shikken in 1224 and as the third shogunal regent he controlled the bakufu for nineteen years, assisted by his uncle Tokifusa. Yasutoki is considered to be the greatest of the Hōjō regents. Tokiyori's tenure and that of Yasutoki have together been called the bakufu's golden age. Tokiyori's oldest son, Tokimune (1251-1284) was the eighth shogunal regent (1268-184) and helped repel the Mongol invasion of Japan." (pp. 10-11, 312, 316) "There were sixteen Hōjō regents or shikken from 1203-1333, during the time of the last seven of the nine Kamakura shoguns and the last fifteen of the sixteen Kamakura-Period emperors. (pp. 257, 259, 260) "The Clear Mirror (Masukagami) is an account of Japanese history from 1185 to 1333 by an anonymous author, almost certainly a court noble writing around the third quarter of the fourteenth century. During this time, the military government at Kamakura controlled the country, maintaining the emperor with his court at Kyoto as symbolic head of state. Though the imperial court had little real power, it attempted to maintain as much of its former dignity and prestige as it could." "The Clear Mirror is at least semi-fictionalized, promoting a picture of a court healthier and more powerful than it really was. Moreover, the work sees the court as guardian of its own traditional arts and lifestyle, and thus provides not only a history of imperial succession and other events but also copious examples of poetic expressions and descriptions of courtly traditions and ceremonies. Because of its attempt to exemplify the best in the courtly prose tradition (it is noted for its imitation of the style of the masterpiece The Tale of Genji), the work has long been valued in Japan as much for its artistic literary contribution as for its historical significance..." Other notes of interest from this book include the following: "In the fifth month, the aromatic leaves of the sweet flag, or clamus, a plant regarded as healthful, were stuffed under eaves as a precaution against hot-weather diseases." (pg. 232, note 12) "Chinese legend tells of three sacred mountains (sanshensan, J. sanshinzan), Penglai, Fangzhang, and Yingzhou, which were inhabited by immortals, and where an elixir of immortality was to be found. A pun on an alternative pronunciation of the characters read sanshinzan: Mikamiyama, the name of a place in Yasu District, Ōmi Province." (pg. 234, note #5 at top) "Kantō. The eight provinces east of the Hakone Pass: Sagami, Musashi, Kōzuke, Shimotsuke, Awa, Kazusa, Shimōsa, and Hitachi. Also a name for the Kamakura bakufu." (pg. 284) "Ōmiya. One of the Hiyoshi shrines. Its principal deity is Ōkuninushi, enshrined there by Saichō, the founder of the Enryakuji Temple on Mt. Hiei, to serve as guardian of the mountain." (pg. 297) "Hiyoshi Shrine(s). Also called Hie and Sannō. A general term for the group of 21 shrines at the eastern foot of Mt. Hiei." (pg. 279) "Enryakuji Temple. Great headquarters of the Tendai sect on Mt. Hiei northeast of the capital [Heian-kyō/Kyoto] on the Yamashiro-Ōmi provincial border; founded in 788 by Saichō (Dengyō Daishi, 767-822)." (pp. 273, 278) A brief somewhat technical synopsis of the play can be found here. Per The Japanese Dance by Marcelle Azra Hincks (London: W. Heinemann; 1910), pg. 20 of "Even the plants which give the drama its title are symbolical of those virtues most loved and encouraged by the monks, for in Japan the plum is the emblem of purity, the cherry represents the Samurai spirit, or spirit of knighthood, and the pine is the symbol of constancy." Per The New Theatre Handbook and Digest of Plays by Bernard Sobel (New York: Crown Publishers; 1959), pg. 338, "Hachi-no-Ki is the only No play that lacks a Mai (a dance of slow steps and solemn gestures simulating the movements of cranes)." Per Historical Dictionary of Japanese Traditional Theatre by Samuel L. Leiter (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006), pg. 220, the dances are termed "Maigoto." "In the early Tokugawa period it was the fashion to wear Kinran O-bis only two and a half inches wide and about six feet long, usually with the design of plum, cherry blossom and pine tree, a romantic idea derived from Hachinoki, a lyrical play." Per An historical sketch of nishiki and kinran brocades by Shojiro Nomura (Boston: Harvard University Fogg Art Museum, 1914), pg. 18. See also this thread about an interesting-shaped menuki. Buddhist teachings in No (Chapter 11 starting on pg. 15) can be found in The Japanese Dance by Marcelle Azra Hincks (London: W. Heinemann, 1910), with Hachi-no-ki ("The Plants")[sic] at pg. 19. Per Japanese Proverbs and Sayings by Daniel Crump Buchanan (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press; 1987), pg. 149, the expression "Iza, Kamakura to iu toki ni wa" (literally, "When it is said, 'Come Now to Kamakura!'") is derived from Hachi-No-Ki and now bears the meaning of "When an emergency arises" or "At a critical moment." For Tsuneyo did say that he would go to Kamakura and assist the army if he was summoned for an emergency. A Japanese e-text of the play itself from a 1928 printing can be found here. And a 1970 NHK recording of the play is available for purchase here as a Region 2 DVD. The earliest known telling of this story in English is found in the Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern edited by Charles Dudley Warner (New York: The International Society, 1897), Vol. XX, Japanese Literature, by Clay MacCauley, in the section Mediæval Literature, pp. 8175-77. "The True Samurai" is prefaced with: "[This illustration of the spirit of the true samurai is taken from a mediæval drama entitled "Dwarf Trees," translated by "Shinehi." The drama tells of the award made to a poverty-striken knight by the de facto ruler of Japan, 1190 [sic], for great kindness shown to the latter when once abroad in the garb of a mendicant priest. The samurai had sacrificed even his dwarf trees to warm his mean-looking guest.]" (What then follows is the second part of Hachi-No-Ki.) The earliest known usage of the term "Hachinoki" in English is found in the The Book of Tea by Kakuzo Okakura (New York: Fox Duffield & Company, 1906), Chap. VI, Flowers, pg. 132. "In Japan, one of the most popular of the No-dances, the Hachinoki, composed during the Ashikaga period, is based upon the story of an impoverished knight, who, on a freezing night, in lack of fuel for a fire, cuts his cherished plants in order to entertain a wandering friar. The friar is in reality no other than Hojo-Tokiyori, the Haroun-Al-Raschid of our tales, and the sacrifice is not without its reward. This opera never fails to draw tears from a Tokio audience even to-day." A description of a witnessed performance of "Hachi-no-ki" ("Trees in Jars") [sic] can be found in Japan at First Hand: Her Islands, Their People, the Picturesque, the Real, with Latest Facts and Figures on Their War-time Trade Expansion and Commercial Outreach by Joseph Ignatius Constantine Clarke (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company; 1918), pg. 140-143. A sequel, of sorts, is mentioned at "Torii Kiyomitsu, Maihime Nidai Hachinoki, 1774" (which references our original ABS article). Per this page from the Omiya Bonsai Museum in Saitama, "A Noh play called Hachi no ki (Potted Plants) was adapted into kabuki plays and joruri dramas during the Edo Period. Among these plays, there are ones called Onna Hachi no ki (Female Version of the 'Potted Plants' Story) in which Tsuneyo Sano, the leading character of the original, was replaced by his wife Shirotae." This Japanese page has a few more details about the play and this page which has a .pdf link to a bi-lingual libretto This one has a manga-flavored portrayal (second row on left) of Harunobu's print (below). This lacquered pen is an homage to the play. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|